Not All Traction is Created Equal

By Nick Adams

If there is one phrase that VCs use when passing on an investment that frustrates founders the most it has to be, “you’re too early;” generally followed up with, “come back when you have more traction.” For what it’s worth, we try to avoid giving this reasoning without explaining why in one additional level of detail. Often times, when I don’t love the timing of the market, or the team doesn’t seem to be well-aligned with the problem that the company is solving, I usually let the founder know that I’m not going to get comfortable leading a [pre-seed/seed] round into that particular space without more proof that the customer pain point is real enough or that the company has a unique advantage against the competition. And that brings us to the dreaded topic of traction.

On more than one occasion I’ve seen founders run off and breathlessly land new users, pilots, and customers only to come back to the VC who sent them out to get traction to find out it’s not enough. Why?

Here are a few common reasons why traction isn’t always the right traction and reduces the ‘quality of revenue’ of your business:

Current revenue is project-based and there isn’t a clear path to recurring revenue

In some situations, it’s a huge asset to get customers to pay for a product that isn’t fully developed. However, structuring a contract on a one-off basis can give the impression that the use case is not repeatable to a broader set of customers.

POCs do not have clear timelines or success criteria

Companies seem to have endless appetites to test new technology without a clear path to a larger implementation. While pilots and POCs have become a painful reality of doing business, save yourself a lot of headache by qualifying the larger opportunity upfront, before committing valuable resources to a pilot that may be nothing more than a science experiment for a bored employee. Ideally, you will get paid for the pilot and negotiate the terms of a larger deal upon successful completion of the pilot. Short of that, be sure to understand the timeline for the pilot, how success will be measured, what is the budget, who is the ultimate buyer, etc.

Contracts are signed but usage of the product is underwhelming

This is an early indication of future churn. Despite going through the hard work of signing annual or multi-year contracts, if your product isn’t solving a clear problem or isn’t being used regularly, then there is probably still a lot of volatility in finding product-market fit. Each dollar of revenue that does not renew is a dollar that needs to be replaced by new sales to continue growing at a meaningful rate which can make for a frustrating sales and marketing hamster-wheel that constantly needs to generate new pipeline to backfill for lost customers and continue growing at 15%+ per month.

Deal sizes are misaligned with the complexity of the sale

If your product requires an enterprise-level sales and marketing strategy then you need to be able to command near 6-figure annual contract values [ACV] to support the cost of those resources. It’s ok to have a land-and-expand strategy where customers start with lower commitments but be prepared to demonstrate your ability to execute the ‘expand’ part of the strategy. Needing enterprise sales resources to close deals that cap out at $25k ACV does not scale. Conversely, trying to use inside sales resources or product-led-growth for a complex sale rarely works.

Existing sales do not align with the future direction of the company

We occasionally see companies that sold a meaningful amount of software [mid six figures to low-seven figures] but are no longer focusing on the legacy product. This is effectively a pivot that won’t be a reliable indicator of future success with the new strategy and will be discounted in valuation negotiations with an investor.

None of these challenges alone is necessarily a deal-breaker for any given investor but be aware of the potential concerns and discuss risk mitigation during fundraising conversations. In today’s startup environment, nearly every “seed” round really has three rounds to it before reaching a Series A. There is often a pre-seed round or angel round, a true seed round, and a late seed round. As investors, one area of risk we need to assess for any potential investment is financing and the biggest risk to the business is often the aforementioned frictions in revenue growth. Our job is to assess which seed round we are investing in and how quickly the company can get to the next phase without having to put in additional bridge round capital to hit the appropriate metrics for Series A and beyond.

Fundraising is very much a game of momentum and, if you’re growing at the right pace, with a high quality of revenue, additional capital will be readily available.

More News & Insights

Differential goes on the record with Lizzy Kolar, the co-founder and CEO of Scope Zero. Scope Zero's mission is to reduce annual utility bills and fuel expenses by $300 billion, the environmental equivalent of removing 125M cars from the road.

Differential goes on the record with Moshe Hecht, an award-winning philanthropic futurist and innovator, reshaping the world of giving through technology and data solutions. The founder and CEO of Hatch, he is a dedicated philanthropist and has been published in Forbes, Guidestar, and Nonprofit Pro.

The WorkplaceTech Spotlight host Hadeel Al-Tashi sits down with Lizzy Kolar, Co-Founder and CEO of Scope Zero to dive into how Scope Zero's Carbon Savings Account (CSA) empowers employees to make affordable home technology and transportation upgrades while aligning with corporate sustainability goals. They discuss how the CSA not only supports environmental and financial wellness for employees but also strengthens a company's commitment to sustainability. Don't miss this opportunity to learn how integrating green benefits can drive meaningful impact within your organization.

On the Record with Nate Cavanaugh, CoFounder & Co-CEO of FlowFi.

In 2021, Nate co-founded of FlowFi, a SaaS-enabled marketplace that connects startups and SMBs with finance experts. FlowFi has raised $10M from top VC firms including Blumberg Capital, Differential Ventures, Clocktower Ventures and Precursor Ventures, and generated 7-figures of annual recurring revenue in its first year.

Nate was nominated to the Forbes 30 Under 30 list for Enterprise Technology.

TECHCRUNCH: FlowFi, a startup creating a marketplace of finance experts for entrepreneurs, closed on $9 million in seed funding.

Blumberg Capital led the investment and was joined by a group of investors including Parade Ventures, Differential Ventures, Precursor Ventures, Special Ventures, 14 Peaks Capital and Cooley LLP.

NASDAQ: Nasdaq TradeTalks: 2024 Cybersecurity Budget Outlook with Almog Apirion, Cyolo.

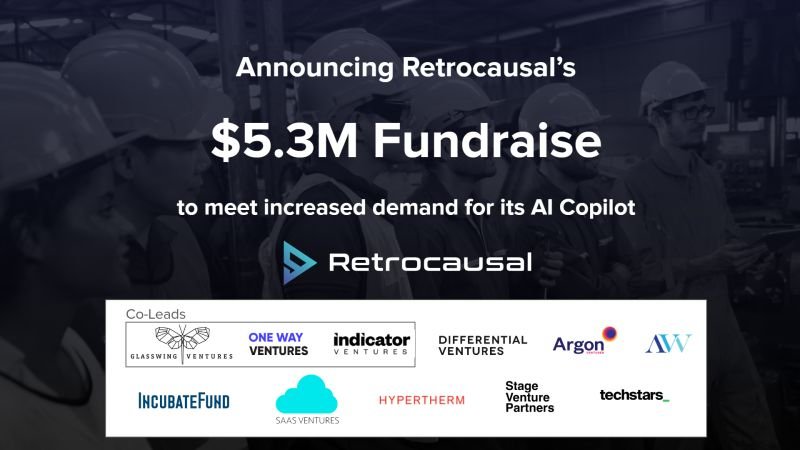

FINSMES: Retrocausal, a Seattle, WA-based platform provider for manufacturing process management, raised $5.3M in funding.

The round was led by Glasswing Ventures, One Way Ventures, and Indicator Ventures, with participation from existing investors Argon Ventures, Differential Ventures, Ascend Vietnam Ventures, Incubate Fund US, SaaS Ventures, Hypertherm Ventures, Stage Venture Partners, and Techstars.

AI and the Future of Work Podcast: Entrepreneurs wonder what it’s like to be a VC. And VCs without an operating background often don’t understand the grit required to turn an idea into a successful business. The best investors have been successful operators first.

Today’s guest is one of those. Nick Adams founded Differential Ventures in 2017 to invest in B2B, data-first seed-stage companies. Since then, Nick and the team have invested in an impressive group of companies including Private AI, Ocrolus, and Agnostiq.

On the Record with Elissa Ross, CoFounder & CEO of Metafold. Elissa Ross is a mathematician and the CEO of Toronto-based startup Metafold 3D. Metafold makes an engineering design platform for additive manufacturing, with an emphasis on supporting engineers using metamaterials, lattices and microstructures at industrial scales. Elissa holds a PhD in discrete geometry (2011), and worked as an industrial geometry consultant for the 8 years prior to cofounding Metafold. Metafold is the result of observations made in the consulting context about the challenges and opportunities of 3D printing.

Nick Adams on PM360: To get a better grasp on what eventual AI regulations could and should look like, PM360 spoke with Nick Adams, Founding Partner at Differential Ventures. In addition to starting the venture capital firm focused on AI/machine learning in 2018, Adams is also a member of the cybersecurity and national security subcommittee for the National Venture Capital Association and recently briefed members of Congress on AI policy and potential regulation.

BETAKIT: Metafold 3D, which wants to make it easier for manufacturers to design and 3D print complex parts, has secured $2.35 million CAD ($1.78 million USD) in seed funding.

Toronto-based Metafold was founded in 2020 by a group of math, geometry, and architecture experts in CEO Elissa Ross, CTO Daniel Hambleton, and COO Tom Reslinski. Born out of Hambleton’s geometry-focused consulting agency, Mesh Consultants, Metafold sells design for additive-manufacturing software to sportswear and biopharmaceutical companies.

Nick Adams on TECHBREW: For all the pixels spilled about the promises of generative AI, it’s starting to feel like we’re telling the same story over and over again. AI is serviceable at document summarization and shows promise in customer service applications. But it generates fictions (the industry prefers the euphemistic and anthropomorphizing term “hallucinates”) and is limited by the data on which it’s trained.

ATLANTA and TEL AVIV, Israel, June 29, 2023 /PRNewswire/ -- Mona, the leading intelligent monitoring platform, unveils a new monitoring solution for GPT-based applications. The free, self-service offering provides businesses with granular visibility into GPT-based products and valuable insights into costs, performance, and quality.

David Magerman on THEINFORMATION: OpenAI’s stated goal is to develop and promote a software system capable of artificial general intelligence. Toward that end, the company has released systems based on large-language models, which can respond to prompts with fluent conversation on many subjects. ChatGPT, Microsoft’s Bing chatbot and other new systems based on OpenAI’s GPT-3 and GPT-4 models are truly incredible and perform far beyond previous attempts at achieving AGI.

BUSINESSWIRE: Morgan Stanley at Work and Carver Edison, a financial technology company, announced today that Shareworks has joined Equity Edge Online® in offering Cashless Participation® to U.S.-based corporate clients. Since the initial launch of Cashless Participation® on Equity Edge Online®, stock plan participants have purchased more than one million shares1 with Cashless Participation®. Now that Shareworks has also launched the tool, a wider cohort of Morgan Stanley at Work corporate clients will have access.

FOX5 WASHINGTON DC: Nick Adams discusses the pros and cons of Artificial intelligence.

PULSE 2.0: Differential Ventures is a seed-stage venture capital fund that was founded by data scientists and entrepreneurs for data-focused entrepreneurs. To learn more about the firm, Pulse 2.0 interviewed Differential Ventures’ managing partner and co-founder Nick Adams.

IoTForAll: Golioth, a leading developer platform for the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), announced open access to a library of new reference designs for embedded engineers to accelerate their time to market, the launch of a Select Partner Program for energy and construction developers, and the completion of a $4.6M round of seed funding led by Blackhorn Ventures and Differential Ventures with participation from existing investors, Zetta Venture Partners, MongoDB Ventures and Lorimer Ventures.

VENTURE BEAT: Data privacy provider Private AI, announced the launch of PrivateGPT, a “privacy layer” for large language models (LLMs) such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT. The new tool is designed to automatically redact sensitive information and personally identifiable information (PII) from user prompts.